Some images die hard. Robert McNamara as the American face of the Vietnam War, announcing troop escalations of 585,000 on June 10, 1968, selling the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution to Congress, and offering his glib definition of success by body count is one of those. With his academician’s wire rimmed glasses and Brooks Brothers suits — Robert McNamara’s persona evoked American imperialism.

The images of the true architects of the Vietnam War, by contrast, are much more congenial, and one might argue that, because of these images, Kennedy with his gorgeous family and Lyndon Johnson pulling the ears of his beloved beagles, are regarded much more benignly in popular history. Robert McNamara was brought in to the Kennedy administration for his managerial abilities rather than his politics. Robert McNamara would have much preferred to have been remembered as the numbers guy who made his life’s mission, as president of the Ford Motor Company, rubbing out the Edsel, than being remembered for being the spark that ignited an American disgrace. But, because of that success at Ford, he was hired to be Secretary of Defense to modernize and streamline the Armed Forces and put the army more firmly under civilian control. Robert McNamara’s task was also to change the focus of our military response from Eisenhower’s policy of Massive Retaliation, to one of tactical non-nuclear flexibility and counter insurgency.

Robert McNamara’s re-organizational goals, however, were preempted by Vietnam and the Cuban Missile Crisis. As someone who admitted how many of his decisions were affected by the Domino Theory, he was no longer an efficiency expert as the one so wonderfully portrayed by Spencer Tracy in DESK SET installing a room-sized computer at a television network. Instead, he became the “technocrat” of the Vietnam War, as former National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzenski has labeled him. McNamara looked at the war in terms of body bags counts, acceptable losses and victory by attrition. He was the first to bring the concept of Systems Analysis to the prosecution of war and into the mainstream of American thought and language.

Nevertheless, being a mere technocrat does not absolve one of responsibility. To the contrary, as the one assigned to the day to day prosecution of the war, McNamara, more than anyone, observed the consequences. And by consequences, I mean senseless death and destruction. As a captain in the Air Force, McNamara was one of those assigned to “vetting” the fire and nuclear bombings (which is technocrat for figuring out how much moral blowback will be generated by the deaths of millions).

So by the time of the Vietnam War, McNamara cannot say he was a stranger to carnage exported by the U.S.A. However, by November of 1967, the technocrat in him realized the numbers didn’t add up. He threw in the towel by recommending a freeze in troop levels; an end to bombing North Vietnam; and a transfer of war operations to the South Vietnamese Army and their cadre of corrupt generals. After the war, “Mac the Knife,” as he was often called derisively, visited Vietnam many times to help the country with reconstruction. Apologists cite those efforts to help and heal as evidence of his redemption.

On the other hand, one might wonder what would have happened if Robert McNamara, a man of massive intelligence and ability, would have applied the moral courage found in his frank analysis and admissions of guilt in the fire bombings of Tokyo and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to the war in Vietnam much earlier than November of 1967? Would his resignation and public condemnation have made a difference? We’ll never know.

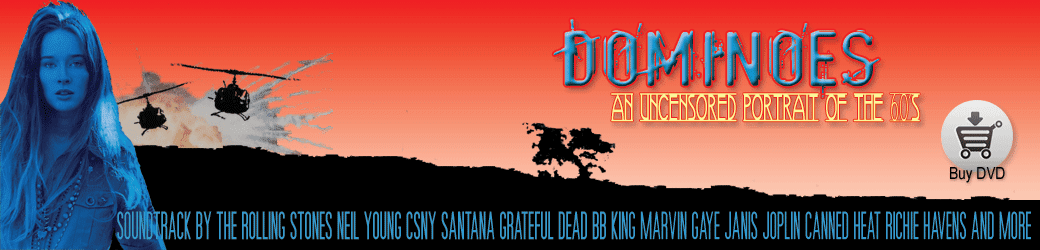

We do know, however, what happened when he kept silent and served his presidents. How ironic it is that, McNamara, the ultimate buttoned-down man, generated so much of the social unrest and change of the 60s. Take a look at the cogent and vividly ironic John Lawrence Ré documentary, aptly named DOMINOES, if you want to experience or re-experience McNamara’s world. Set to 60’s anthems, the film is a searing, heart breaking and incisive look at what happens when ideologues rule and technocrats serve.

Perhaps Robert McNamara would just refer to the decade of the 60s as collateral damage.

No comments:

Post a Comment